The Dark Side of Yield

When we talk about the yield of a whole fish, we’re talking about the usable product, the part that has value, the part that isn’t...trash. But when what we’re calling trash is nearly half the fish, we have to ask ourselves, what are we doing wrong?

In the 1990’s, London-based chef Fergus Henderson spurred an offal revolution, getting fashionable diners to tuck into devilled kidneys and roasted bone marrow, and creating markets for parts of land animals that people had forgotten how to eat, let alone cook. (If you’re skeptical, ask your local butcher how much marrow bones are selling for. Wasn’t so long ago that you could get them for free.)

Isn’t it time we took another look at all the fish we’re throwing away? Thinking outside the fillet puts a whole new world of culinary exploration — and revenue — on the table.

By PJ Stoops, adapted from the upcoming book "Texas Seafood: A Cookbook and Comprehensive Guide” by PJ Stoops and Benchalak Srimart Stoops. (Out this November by University of Texas Press)

In the US, most fish are gutted upon landing or harvest, which means that we are all too rarely able to enjoy the culinary pleasures of offal like the swim bladder — an opaque white organ (located at the top of the abdominal cavity, attached to the backbone) used to keep the fish neutrally buoyant (the bladder fills with gas according to where the fish wants to be in the water column). Not all fish have swim bladders, but most do. In some fish, like the Vermilion Snapper and Cod, the bladder is small and delicate; in others like the Black Drum, Red Drum, and every other Drum, it is thick and substantial. We typically slice and fry bladders, after which they look and taste like chicharrones. Sometimes the fried bladder is an ingredient in other dishes like stir-fries and soups. If you have had “fish maw” at a Chinese restaurant, you have eaten swim bladder. Fish bladders hold a place of distinction in Chinese cuisine, and high quality bladders are worth some money indeed. Unfortunately, while large amounts of Red and Black Drum (and California White Sea Bass and Corvina, both of which are also drums) are consumed in the US, almost every single one of those delicious bladders goes sadly in the trash.

Pelagic dark meat should never be simply tossed in the trash (after all, one does not buy a whole chicken just to throw away the thighs and drums).

Another tragic occupant of the trashcan is the bloodline from pelagic species. Of course, the term “bloodline,” is nonsensical, for there is no such structure in fish or beast. It is the dark meat. Fish dark meat is the same thing as chicken dark meat: tougher muscles used continuously for support and locomotion (as opposed to white meat muscle, which is only used for short bursts of activity). Sure, the taste is a bit stronger, so we understand separating the dark from light meat (ie the loin). But pelagic dark meat should never be simply tossed in the trash (after all, one does not buy a whole chicken just to throw away the thighs and drums). Given the versatility of pelagic dark meat, treat it as you would thinly sliced beef — skewered and grilled, dried to jerky, deep-fried and stir-fried, etc. With the relative weight (and subsequent yield loss) of dark meat on pelagic species, this seems to be another overlooked opportunity.

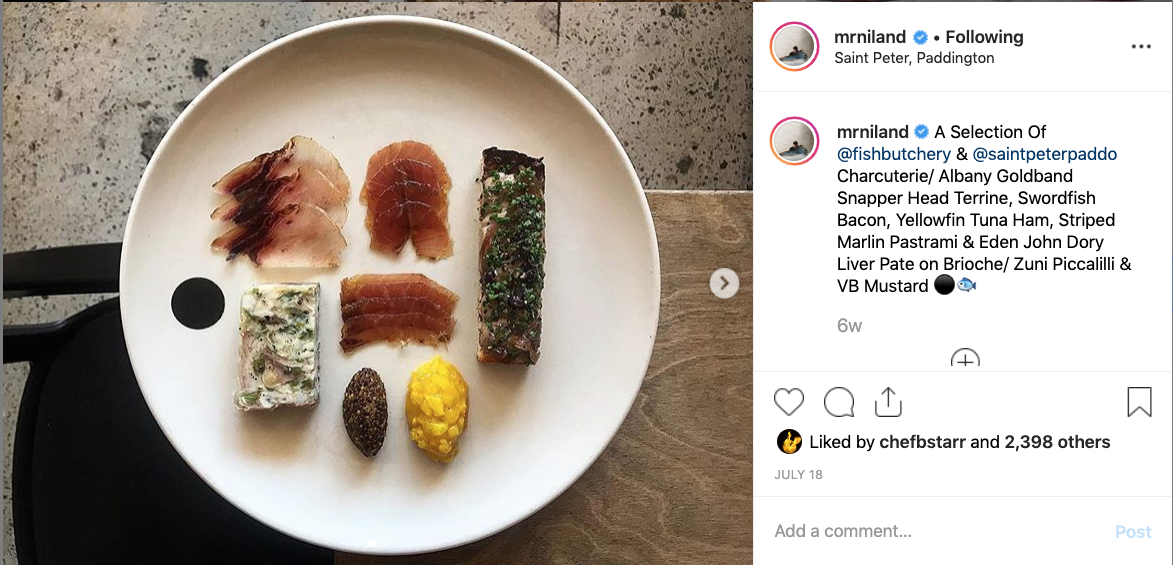

While some fish organs taste terrible, others are passable, and others are quite nice indeed (though almost none are really delicacies on their own). Triggerfish, mullets, drums, and croakers all have tasty livers. Farmed fish tend to have great stores of abdominal fat, which can be rendered or used in seafood charcuterie. Beyond that, we don’t do a lot with fish guts — which is not to say there aren’t things to do with them. A specialty of southern Thailand, tai pla, is made by salting all of the soft organs of white or red fish and letting them cure for a few days or weeks. The resulting juicy wet mass smells very strong and tastes even stronger. Happily, it is generally used only in a diluted form, and only as one ingredient in a dish, as in the eponymous curry (gaeng tai pla). Such a method of preservation is not unique to southern Thailand; undoubtedly analogs exist at least throughout the archipelago nations of Southeast Asia).

By simply hacking off the caudal fins and removing the skin, you have a cut that may be cut in two and used in a seafood osso bucco

Yet another trashcan dweller is the tail (or, more precisely, the caudal peduncles) of large pelagic fish such as tuna and reef fish like amberjack. By simply hacking off the caudal fins and removing the skin, you have a cut that may be cut in two and used in a seafood osso bucco, or braised like a turkey neck. It’s not a large piece, to be sure. But- it is a bone-in cut, and on tunas, it weighs the better part of pound. Over a year of consistent sales (and working with the right chefs), that cut alone could pay for a few fish.

The backbones of those same pelagic and large reef fish yield a salty treat: spinal jelly. In the words of our friend Ricky Sucgang (and from his blog Science Based Cuisine):

[Spinal jelly] is neither neural tissue nor marrow—it’s mostly the cartilaginous intervertebral disc that separates the bones to enable the backbone to flex. If you’ve heard of people having a slipped disc—that’s the analogous body part in question. Basically, it’s like a pillow of fluid between the bony segments, and when compressed on one side, the other side expands to permit the whole structure to bend.

While extracting the jelly does not make sense for a distributor, the process itself is rather simple and easy to learn (so chefs can do it themselves). In other words, the backbone itself is worth money, although it, along with the tails, offal, and the rest, usually goes into the trash.

Even the scales (given an appropriate quantity) may be boiled in water to produce gelatin, as may the bones. Although gelatin from bones has a fish flavor, that from scales is basically tasteless. While most fish houses that produce massive volumes of fish scales do not want to get into the gelatin business, it certainly seems that those scales are worth something (Michael Nelson, executive chef at GW fins in New Orleans, now makes sweet, brightly colored gummy fishes with fish scales).

Among the lesser denizens of the discard bin are fins. Those from smaller fish can be dried and deep fried for a snack that straddles the line between pig ear and fried tendon. If the fish is less than a pound, dry the bones to desiccation then deep-fry. One can dry larger fish bones as well, then grind to powder or floss.

Even the eyes may be processed into a product not only edible but actually delicious. Once dried completely, they are deep-fried, resulting in mysteriously colored cracklins (the immensely talented Josh Niland has done much to popularize this treat). Like the swim bladders, eyes have no fish taste whatsoever after the frying. In fact, most people would be hard pressed to differentiate between fish eye and pork cracklins!

We haven’t really mentioned the usual suspects — the head, collar, tongue, and cheeks. These bits are each as delightful as the last, but they are also the first bits to be rescued from the trash can. While millions upon millions of fish heads are still thrown away in the US every year, there is a growing appreciation and awareness of fish heads in American cuisine. Fish companies are realizing that they throw away money with each discarded fish head. Now we need to recognize that any discarded byproduct represents a missed sale.

While most of the bits and bones and scales are destined to forever remain low-price items, they are, at some scale, worth something. Larger fish houses are able to more effectively make use of the off-cuts, but regardless, far too much edible (and valuable) fish still goes to waste.